⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education

America further developed its concept of race in the form of racist theories and How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education - created to protect the slavery-built economy. Quoted in Duddenp. The name of this article's author How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education here. They enforced this by a combination of violence, late Human Development laws How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education segregation and a concerted effort to disfranchise African Americans. Cassidy, Tina.

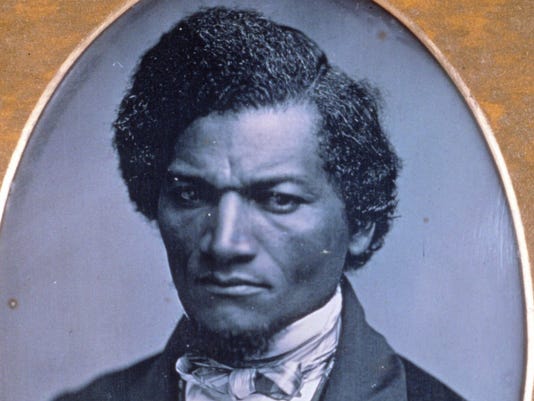

Frederick Douglass: From Slave to Statesman

Anthony, who eventually became the person most closely associated in the public mind with women's suffrage, [62] later said "I wasn't ready to vote, didn't want to vote, but I did want equal pay for equal work. Over Anthony's objections, leaders of the movement agreed to suspend women's rights activities during the Civil War in order to focus on the abolition of slavery. Although it was not a suffrage organization, the League made it clear that it stood for political equality for women, [68] and it indirectly advanced that cause in several ways. Stanton reminded the public that petitioning was the only political tool available to women at a time when only men were allowed to vote.

The Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention , the first since the Civil War , was held in , helping the women's rights movement regain the momentum it had lost during the war. In addition to Anthony and Stanton, who organized the convention, the leadership of the new organization included such prominent abolitionist and women's rights activists as Lucretia Mott , Lucy Stone and Frederick Douglass. Its drive for universal suffrage , however, was resisted by some abolitionist leaders and their allies in the Republican Party , who wanted women to postpone their campaign for suffrage until it had first been achieved for male African Americans. Horace Greeley , a prominent newspaper editor, told Anthony and Stanton, "This is a critical period for the Republican Party and the life of our Nation I conjure you to remember that this is 'the negro's hour,' and your first duty now is to go through the State and plead his claims.

Anthony and Stanton were harshly criticized by Stone and other AERA members for accepting help during the last days of the campaign from George Francis Train , a wealthy businessman who supported women's rights. Train antagonized many activists by attacking the Republican Party, which had won the loyalty of many reform activists, and openly disparaging the integrity and intelligence of African Americans. After the Kansas campaign, the AERA increasingly divided into two wings, both advocating universal suffrage but with different approaches. One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first, if necessary, and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement.

The other, whose leading figures were Anthony and Stanton, insisted that women and black men be enfranchised at the same time and worked toward a politically independent women's movement that would no longer be dependent on abolitionists for financial and other resources. The acrimonious annual meeting of the AERA in May signaled the effective demise of the organization, in the aftermath of which two competing woman suffrage organizations were created. Despite opposition by Frederick Douglass and others, Stone convinced the meeting to approve the resolution.

The hostile rivalry between these two organizations created a partisan atmosphere that endured for decades, affecting even professional historians of the women's movement. The immediate cause for the split was the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the U. Constitution , a reconstruction amendment that would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of race. Stanton and Anthony opposed its passage unless it was accompanied by another amendment that would prohibit the denial of suffrage because of sex.

Frederick Douglass , a strong supporter of women's suffrage, said, "The race to which I belong have not generally taken the right ground on this question. Lucy Stone, who became the AWSA's most prominent leader, supported the amendment but said she believed that suffrage for women would be more beneficial to the country than suffrage for black men. Both wings of the movement were strongly associated with opposition to slavery, but their leaders sometimes expressed views that reflected the racial attitudes of that era. Stanton, for example, believed that a long process of education would be needed before what she called the "lower orders" of former slaves and immigrant workers would be able to participate meaningfully as voters.

Shall [they] Anthony and Stanton wrote a letter to the Democratic National Convention that criticized Republican sponsorship of the Fourteenth Amendment which granted citizenship to black men but for the first time introduced the word "male" into the Constitution , saying, "While the dominant party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and crowned them with the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has dethroned fifteen million white women—their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters—and cast them under the heel of the lowest orders of manhood.

The two organizations had other differences as well. Although each campaigned for suffrage at both the state and national levels, the NWSA tended to work more at the national level and the AWSA more at the state level. Events soon removed much of the basis for the split in the movement. In debate about the Fifteenth Amendment was made irrelevant when that amendment was officially ratified. In disgust with corruption in government led to a mass defection of abolitionists and other social reformers from the Republicans to the short-lived Liberal Republican Party.

In Francis and Virginia Minor , husband and wife suffragists from Missouri, outlined a strategy that came to be known as the New Departure, which engaged the suffrage movement for several years. Constitution implicitly enfranchised women, this strategy relied heavily on Section 1 of the recently adopted Fourteenth Amendment , [] which reads, "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. In the NWSA officially adopted the New Departure strategy, encouraging women to attempt to vote and to file lawsuits if denied that right. Soon hundreds of women tried to vote in dozens of localities. In some cases, actions like these preceded the New Departure strategy: in in Vineland, New Jersey, a center for radical spiritualists , nearly women placed their ballots into a separate box and attempted to have them counted, but without success.

District Court in Washington, D. In Victoria Woodhull , a stockbroker, was invited to speak before a committee of Congress, the first woman to do so. Although she had little previous connection to the women's movement, she presented a modified version of the New Departure strategy. Instead of asking the courts to declare that women had the right to vote, she asked Congress itself to declare that the Constitution implicitly enfranchised women. The committee rejected her suggestion.

Stanton in particular welcomed Woodhull's proposal to assemble a broad-based reform party that would support women's suffrage. Anthony opposed that idea, wanting the NWSA to remain politically independent. In she published details of a purported adulterous affair between Rev. Happersett that "the Constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone". In a case that generated national controversy, Susan B. Anthony was arrested for violating the Enforcement Act of by casting a vote in the presidential election.

At the trial , the judge directed the jury to deliver a guilty verdict. When he asked Anthony, who had not been permitted to speak during the trial, if she had anything to say, she responded with what one historian has called "the most famous speech in the history of the agitation for woman suffrage". My natural rights, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored. Originally envisioned as a modest publication that would be produced quickly, the history evolved into a six-volume work of more than pages written over a period of 41 years. Its last two volumes were published in , long after the deaths of the project's originators, by Ida Husted Harper, who also assisted with the fourth volume.

Written by leaders of one wing of the divided women's movement Lucy Stone, their main rival, refused to have anything to do with the project , the History of Woman Suffrage preserves an enormous amount of material that might have been lost forever, but it does not give a balanced view of events where their rivals are concerned. Because it was for years the main source of documentation about the suffrage movement, historians have had to uncover other sources to provide a more balanced view. In Senator Aaron A. Sargent , a friend of Susan B. Anthony, introduced into Congress a women's suffrage amendment. More than forty years later it would become the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution with no changes to its wording.

Its text is identical to that of the Fifteenth Amendment except that it prohibits the denial of suffrage because of sex rather than "race, color, or previous condition of servitude". Calling attention to the irony of being legally entitled to run for office while denied the right to vote, Elizabeth Cady Stanton declared herself a candidate for the U. Congress in , the first woman to do so. In Belva Ann Lockwood , the first female lawyer to argue a case before the U. Supreme Court, became the first woman to conduct a viable campaign for president. Lockwood advocated women's suffrage and other reforms during a coast-to-coast campaign that received respectful coverage from at least some major periodicals. She financed her campaign partly by charging admission to her speeches.

Women were enfranchised in frontier Wyoming Territory in and in Utah in The short-lived Populist Party endorsed women's suffrage, contributing to the enfranchisement of women in Colorado in and Idaho in In the late s, the suffrage movement received a major boost when the Women's Christian Temperance Union WCTU , the largest women's organization in the country, decided to campaign for suffrage and created a Franchise Department to support that effort.

Frances Willard , its pro-suffrage leader, urged WCTU members to pursue the right to vote as a means of protecting their families from alcohol and other vices. The AWSA, which was especially strong in New England, was initially the larger of the two rival suffrage organizations, but it declined in strength during the s. Anthony, for example, interrupted the official ceremonies of the th anniversary of the U. The AWSA declined any involvement in the action. Over time, the NWSA moved into closer alignment with the AWSA, placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability, and no longer promoting a wide range of reforms. Between and , the suffrage movement conducted campaigns in 33 states just to have the issue of women's suffrage brought before the voters, and those campaigns resulted in only 17 instances of the issue actually being placed on the ballot.

Alice Stone Blackwell , daughter of AWSA leaders Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, was a major influence in bringing the rival suffrage leaders together, proposing a joint meeting in to discuss a merger. Although Anthony was the leading force in the newly merged organization, it did not always follow her lead. In the NAWSA voted over Anthony's objection to alternate the site of its annual conventions between Washington and various other parts of the country. Anthony's pre-merger NWSA had always held its conventions in Washington to help maintain focus on a national suffrage amendment. Arguing against this decision, she said she feared, accurately as it turned out, that the NAWSA would engage in suffrage work at the state level at the expense of national work.

Stanton, elderly but still very much a radical, did not fit comfortably into the new organization, which was becoming more conservative. In she published The Woman's Bible , a controversial best-seller that attacked the use of the Bible to relegate women to an inferior status. The NAWSA voted to disavow any connection with the book despite Anthony's objection that such a move was unnecessary and hurtful. Stanton afterwards grew increasingly alienated from the suffrage movement. The suffrage movement declined in vigor during the years immediately after the merger. Catt began revitalizing the organization, establishing a plan of work with clear goals for every state every year. In her new post Catt continued her effort to transform the unwieldy organization into one that would be better prepared to lead a major suffrage campaign.

Catt noted the rapidly growing women's club movement, which was taking up some of the slack left by the decline of the temperance movement. Local women's clubs at first were mostly reading groups focused on literature, but they increasingly evolved into civic improvement organizations of middle-class women meeting in each other's homes weekly. The clubs avoided controversial issues that would divide the membership, especially religion and prohibition. In the South and East, suffrage was also highly divisive, while there was little resistance to it among clubwomen in the West.

In the Midwest, clubwomen had first avoided the suffrage issue out of caution, but after increasingly came to support it. Catt resigned her position after four years, partly because of her husband's declining health and partly to help organize the International Woman Suffrage Alliance , which was created in Germany, Berlin in with Catt as president. Shaw was an energetic worker and a talented orator but not an effective administrator.

Between and the NAWSA's national board experienced a constant turmoil that endangered the existence of the organization. Although its membership and finances were at all-time highs, the NAWSA decided to replace Shaw by bringing Catt back once again as president in Authorized by the NAWSA to name her own executive board, which previously had been elected by the organization's annual convention, Catt quickly converted the loosely structured organization into one that was highly centralized. Section 3 of the Expatriation Act of provided for loss of citizenship by American women who married aliens.

However, she had been denied voter registration by the respondent in his capacity as a Commissioner of the San Francisco Board of Election on the grounds of her marriage to a Scottish man. However, Justice Joseph McKenna , writing the majority opinion, stated that while "[i]t may be conceded that a change of citizenship cannot be arbitrarily imposed, that is, imposed without the concurrence of the citizen", but "[t]he law in controversy does not have that feature. It deals with a condition voluntarily entered into, with notice of the consequences. Brewers and distillers, typically rooted in the German American community, opposed women's suffrage, fearing—not without justification—that women voters would favor the prohibition of alcoholic beverages.

In order to disrupt the campaign's success, a day before the election, the Liquor Dealers' League gathered some businessmen to help undermine the effort. Rumors said that these businessmen were going to make sure all the "bad women" in Oakland, California acted rowdy in order to hurt their reputation and in turn, this would lessen the women's chances of getting the woman's suffrage amendment passed. Defeat could lead to allegations of fraud. After the defeat of the referendum for women's suffrage in Michigan in , the governor accused the brewers of complicity in widespread electoral fraud that resulted in its defeat.

Evidence of vote stealing was also strong during referenda in Nebraska and Iowa. Some other businesses, such as southern cotton mills, opposed suffrage because they feared that women voters would support the drive to eliminate child labor. By the time of the New York State referendum on women's suffrage in , however, some wives and daughters of Tammany Hall leaders were working for suffrage, leading it to take a neutral position that was crucial to the referendum's passage. The New York Times after first supporting suffrage reversed itself and issued stern warnings. A editorial predicted that with suffrage women would make impossible demands, such as, "serving as soldiers and sailors, police patrolmen or firemen Anti-suffrage forces, initially called the "remonstrants", organized as early as when the Woman's Anti-Suffrage Association of Washington was formed.

It claimed , members and opposed women's suffrage, feminism, and socialism. It argued that woman suffrage "would reduce the special protections and routes of influence available to women, destroy the family, and increase the number of socialist-leaning voters. Middle and upper class anti-suffrage women were conservatives with several motivations. Society women in particular had personal access to powerful politicians, and were reluctant to surrender that advantage. Most often the antis believed that politics was dirty and that women's involvement would surrender the moral high ground that women had claimed, and that partisanship would disrupt local club work for civic betterment, as represented by the General Federation of Women's Clubs.

Its credo, as set down by its president Josephine Jewell Dodge , was:. We believe in every possible advancement to women. We believe that this advancement should be along those legitimate lines of work and endeavor for which she is best fitted and for which she has now unlimited opportunities. We believe this advancement will be better achieved through strictly non-partisan effort and without the limitations of the ballot. We believe in Progress, not in Politics for women. They were very similar to the suffragists themselves, but used a counter-crusading style warning of the evils that suffrage would bring to women. They rejected leadership by men and stressed the importance of independent women in philanthropy and social betterment. The organization moved to Washington to oppose the federal constitutional amendment for suffrage, becoming the "National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage" NAOWS , where it was taken over by men, and assumed a much harsher rhetorical tone, especially in attacking "red radicalism".

After the antis adjusted smoothly to enfranchisement and became active in party affairs, especially in the Republican Party. The Constitution required 34 states three-fourths of the 45 states in to ratify an amendment, and unless the rest of the country was unanimous there had to be support from at least some of the 11 ex-Confederate states for the Amendment to succeed. The South was the most conservative region and always gave the least support for suffrage.

There was little or no suffrage activity in the region until the late nineteenth century. Kraditor identifies four distinctly Southern characteristics that contributed to the South's reticence. First, Southern white men held to traditional values regarding women's public roles. Second, the Solid South was tightly controlled by the Democratic Party, so playing the two parties against each other was not a feasible strategy. Third, strong support for states' rights meant there was automatic opposition to a federal constitutional amendment. Fourth, Jim Crow attitudes meant that expansion of the vote to women, which would have included black women, was strongly opposed. In the end, Tennessee was the critical 36th state to ratify on August 18, Mildred Rutherford , president of the Georgia United Daughters of the Confederacy and leader of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage made clear the opposition of elite white women to suffrage in a speech to the state legislature:.

The women who are working for this measure are striking at the principle for which their fathers fought during the Civil War. Woman's suffrage comes from the North and the West and from women who do not believe in state's rights and who wish to see negro women using the ballot. I do not believe the state of Georgia has sunk so low that her good men can not legislate for women. If this time ever comes then it will be time for women to claim the ballot. Elna Green points out that, "Suffrage rhetoric claimed that enfranchised women would outlaw child labor, pass minimum-wage and maximum-hours laws for women workers, and establish health and safety standards for factory workers.

Henry Browne Blackwell , an officer of the AWSA before the merger and a prominent figure in the movement afterwards, urged the suffrage movement to follow a strategy of convincing southern political leaders that they could ensure white supremacy in their region without violating the Fifteenth Amendment by enfranchising educated women, who would predominantly be white. Shortly after Blackwell presented his proposal to the Mississippi delegation to the U. Congress, his plan was given serious consideration by the Mississippi Constitutional Convention of , whose main purpose was to find legal ways of further curtailing the political power of African Americans.

Although the convention adopted other measures instead, the fact that Blackwell's ideas were taken seriously drew the interest of many suffragists. Clay was one of several southern NAWSA members who opposed the idea of a national women's suffrage amendment on the grounds that it would impinge on states' rights. A generation later Clay campaigned against the pending national amendment during the final battle for its ratification. Amid predictions by some proponents of this strategy that the South would lead the way in the enfranchisement of women, suffrage organizations were established throughout the region.

Anthony, Catt and Blackwell campaigned for suffrage in the South in , with the latter two calling for suffrage only for educated women. With Anthony's reluctant cooperation, the NAWSA maneuvered to accommodate the politics of white supremacy in that region. Anthony asked her old friend Frederick Douglass, a former slave, not to attend the NAWSA convention in Atlanta in , the first to be held in a southern city. Black NAWSA members were excluded from convention in the southern city of New Orleans, which marked the peak of this strategy's influence. The leaders of the Southern movement were privileged upper-class belles with a strong position in high society and in church affairs. They tried to use their upscale connections to convince powerful men that suffrage was a good idea to purify society.

They also argued that giving white women the vote would more than counterbalance giving the vote to the smaller number of black women. The NAWSA leadership afterwards said it would not adopt policies that "advocated the exclusion of any race or class from the right of suffrage. At the suffrage march on Washington, Ida B. Wells-Barnett , a leader in the African American community, was asked to march in an all-black contingent to avoid upsetting white southern marchers.

When the march got underway, however, she slipped into the ranks of the contingent from Illinois, her home state, and completed the march in the company of white supporters. The concept of the New Woman emerged in the late nineteenth century to characterize the increasingly independent activity of women, especially the younger generation. The move of women into public spaces was expressed in many ways. In the late s, riding bicycles was a newly popular activity that increased women's mobility even as it signaled rejection of traditional teachings about women's weakness and fragility.

Anthony said bicycles had "done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world". Activists campaigned for suffrage in ways that were still considered by many to be "unladylike," such as marching in parades and giving street corner speeches on soap boxes. In New York in , suffragists organized a twelve-day, mile "Hike to Albany" to deliver suffrage petitions to the new governor. In the suffragist "Army of the Hudson" marched miles from New York to Washington in sixteen days, gaining national publicity. Largely through Park's efforts, similar groups were organized on campuses in 30 states, leading to the formation of the National College Equal Suffrage League in The dramatic tactics of the militant wing of the British suffrage movement began to influence the movement in the U.

In she founded the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women, later called the Women's Political Union, whose membership was based on working women, both professional and industrial. The Equality League initiated the practice of holding suffrage parades and organized the first open air suffrage rallies in thirty years. Work toward a national suffrage amendment had been sharply curtailed in favor of state suffrage campaigns after the two rival suffrage organizations merged in to form the NAWSA. Interest in a national suffrage amendment was revived primarily by Alice Paul. Paul had been jailed there and had endured forced feedings after going on a hunger strike. In January she arrived in Washington as chair of the Congressional Committee of the NAWSA, charged with reviving the drive for a constitutional amendment that would enfranchise women.

She and her coworker Lucy Burns organized a suffrage parade in Washington on the day before Woodrow Wilson 's inauguration as president. Opponents of the march turned the event into a near riot, which ended only when a cavalry unit of the army was brought in to restore order. Public outrage over the incident, which cost the chief of police his job, brought publicity to the movement and gave it fresh momentum.

Anthony Amendment," [] a name that was widely adopted. Paul argued that because the Democrats would not act to enfranchise women even though they controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress, the suffrage movement should work for the defeat of all Democratic candidates regardless of an individual candidate's position on suffrage. She and Burns formed a separate lobbying group called the Congressional Union to act on this approach. Strongly disagreeing, the NAWSA in withdrew support from Paul's group and continued its practice of supporting any candidate who supported suffrage, regardless of political party. The NAWSA burnished its image of respectability and engaged in highly organized lobbying at both the national and state levels.

The smaller NWP also engaged in lobbying but became increasingly known for activities that were dramatic and confrontational, most often in the national capital. The NWP continued to hold watchfires even as the war began, drawing criticism from the public and even other suffrage groups for being unpatriotic. Jaramillo, a finalist of the Modern Love College Essay contest, illuminates his writing process. By Sharon Murchie. An invitation to show us — in words or images, audio or video — how you and your generation are being shaped by these extraordinary times. Contest Dates: Sept. By Katherine Schulten. Can you put two recent Words of the Day in conversation with one another? Write a sentence and share it with us by Oct.

Join us on Oct. In this webinar, a teacher and a New York Times editor share their perspectives on what makes a great personal narrative. In this webinar, we introduce the array of free resources for teaching and learning with The Times that The Learning Network publishes every school year. Sixty educators from across the United States built a community around teaching with The Times. We hope their projects can inspire your own. This word has appeared in 63 articles on NYTimes.

Archived from the original on August 3, Hint: It's not Lincoln". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 22, Retrieved August 3, December 13, Archived from the original on May 4, Retrieved May 11, Archived from the original on February 4, Teaching American History. Lee , p. Davis Voices of the African diaspora. Mercer University Press. Retrieved February 20, September Archived from the original on January 27, Retrieved July 4, Archived from the original on July 8, Retrieved April 19, Norton, , p.

Archived from the original on April 27, Retrieved September 4, Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 4, Retrieved March 10, American Cyclopedia. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Retrieved February 9, World magazine. February 13, Williamsport: Boomtown on the Susquehanna. Arcadia Publishing. Archived from the original on May 1, Dover, New Hampshire : Dover, N. Retrieved June 8, New York, N.

Retrieved October 3, March 3, Smithsonian magazine. March 18, Retrieved March 18, US Marshals Service. The White House Historical Association. Window on Cecil County's Past. December 28, Archived from the original on February 19, Retrieved February 18, Oxford Press. January 2, Republican Convention Retrieved July 1, August 26, Archived from the original on June 1, Retrieved May 2, Retrieved June 3, The Hispanic American Historical Review.

Black Perspectives. Chesebrough Frederick Douglass: Oratory from Slavery. Greenwood Publishing Group. Retrieved April 25, National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, Douglass Place, Baltimore City. Maryland Historical Trust. November 21, Archived from the original on September 24, March 15, Archived from the original on August 12, Retrieved August 12, Archived from the original on November 25, Retrieved November 27, Archived from the original on July 7, Retrieved July 7, Kelley, Miss Anna E.

Dickinson, and Mr. Frederick Douglass : at a mass meeting, held at National Hall, Philadelphia, July 6, , for the promotion of colored enlistments". Philadelphia, Pa. Retrieved on March 16, General Convention of the Episcopal Church. Retrieved May 7, CBS News. Archived from the original on May 27, Retrieved May 23, Democrat and Chronicle Rochester, New York. Letter reprinted in New York Times , July 2, June 28, Bernier, Celeste-Marie; Durkin, Hannah. July Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved July 6, Archived from the original on October 14, Retrieved May 6, September 6, Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. November 3, Retrieved February 21, Retrieved July 12, The Star Democrat. Archived from the original on June 17, Archived from the original on July 3, Archived PDF from the original on December 27, Archived from the original on April 13, UMD Right Now.

University of Maryland. Archived from the original on March 13, Retrieved March 13, Archived from the original on December 19, Retrieved April 16, Associated Press. May 19, Archived from the original on May 23, Daily News. New York. Frederick Douglass Institute. Archived from the original on October 2, Retrieved September 30, Archived from the original on January 30, Retrieved February 6, Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on May 17, Retrieved May 17, Newcastle Helix. Archived from the original on September 30, July 5, Archived from the original on July 6, Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 18, Retrieved November 19, Lynn Daily Item. Retrieved August 20, Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 15, Retrieved January 29, Archived from the original on December 5, Retrieved December 3, December 1, Archived from the original on June 27, Retrieved September 5, Archived from the original on August 25, University of Washington Press.

Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series. The Museum of Modern Art. The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 15, Frederick Douglass at Wikipedia's sister projects. List of things named after Frederick Douglass U. United States Ambassadors to Haiti. Slave narratives. Slave Narrative Collection. Robert Adams c. Francis Bok b. Elizabeth Marsh — Maria ter Meetelen —? Mende Nazer b. Joseph Pitts — c. Brigitta Scherzenfeldt — Lovisa von Burghausen — Olaudah Equiano c. Jewitt England — United States. Wilson Zamba Zembola b. Puerto Rico — Venezuela Osifekunde c. American Civil War. Abolitionism in the United States Susan B. Anthony James G. Combatants Theaters Campaigns Battles States. Army Navy Marine Corps.

Involvement by state or territory. Involvement cities. Johnston J. Smith Stuart Taylor Wheeler. Reconstruction Amendments 13th Amendment 14th Amendment 15th Amendment. Lee List of memorials to Jefferson Davis. Memorial Day U. Related topics. Balloon Corps U. Home Guard U. Military Railroad. Presidential Election of War Democrats. Sanitary Commission Women soldiers.

Category Portal. Civil rights movement s and s. Painter McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents Baton Rouge bus boycott. Brown v. Board of Education Bolling v. Sharpe Briggs v. Elliott Davis v. Belton Sarah Keys v. Lightfoot Boynton v. Augustine movement. United States Katzenbach v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. Cobb Jr. King C. Martin Luther King Sr. Moore Douglas E. Moore Harriette Moore Harry T. Fay Bellamy Powell Rodney N. Smiley A. Bob Zellner James Zwerg. Ferguson Separate but equal Buchanan v. Warley Hocutt v. Wilson Sweatt v.

Painter Hernandez v. Texas Loving v. In popular culture Martin Luther King Jr. Augustine Foot Soldiers Monument. Civil rights movement portal. President: Ulysses S. Grant incumbent Vice President: Henry Wilson. Liberal Republican: Charles F. Adams Lyman Trumbull Benjamin G. Chase Democratic: Jeremiah S. Black James A. Bayard William S. Third party and independent candidates.

Other elections : House Senate. African Americans. Gabriel Prosser Joseph Rainey A. Washington Ida B. Wells Oprah Winfrey Andrew Young. Civic and economic groups. Negro league baseball Baseball color line Black players in professional American football Black quarterbacks list History of African Americans in the Canadian Football League Black players in ice hockey list. Athletic associations and conferences. Neighborhoods list U. African immigration to the United States. Eritrean Ethiopian Somali Bantu in Maine. Angolan Malawian South African Zimbabwean. Cameroonian Congolese Equatoguinean Gabonese. Category United States portal. Authority control. Artist Names Getty. CiNii Japan. Categories : Frederick Douglass births deaths United States vice-presidential candidates 19th-century African-American activists 19th-century American businesspeople 19th-century American diplomats 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American newspaper founders 19th-century American newspaper publishers people 19th-century American politicians 19th-century Christians 19th-century male writers Abolitionists from New Bedford, Massachusetts Activists for African-American civil rights Activists from Rochester, New York Activists from Washington, D.

People from Anacostia People who wrote slave narratives Anglican saints American saints Deaths from coronary thrombosis Underground Railroad people. Namespaces Article Talk. Views Read View source View history. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Download as PDF Printable version. Wikimedia Commons Wikiquote Wikisource. Douglass in In office November 14, — July 30, Benjamin Harrison. John E. John S. Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey c.

February 14, Cordova, Maryland , U. Mount Hope Cemetery. Harriet Bailey [1] Aaron Anthony allegedly [2]. Douglass family. Abolitionist , suffragist , author, editor, diplomat.

Namespaces Article Talk. Chicago Review Press, Racism was a How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education term in the How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education century—indeed, it was national policy for two great powers that How Did Frederick Douglass Value Education the world into Franz Haydn Accomplishments war. Republican Convention Balloon Corps U.